|

tanding

on

top

of

the Newgate with

our

backs

to

the

city,

we

observe

a

curious

semi-circular

form

recessed

into

the

green

space

before

us.

Unimpressive as it may look now, this

is

actually the

partially-excavated

remains

of

the

largest

stone-built

Roman

military

amphitheatre

in

Britain. tanding

on

top

of

the Newgate with

our

backs

to

the

city,

we

observe

a

curious

semi-circular

form

recessed

into

the

green

space

before

us.

Unimpressive as it may look now, this

is

actually the

partially-excavated

remains

of

the

largest

stone-built

Roman

military

amphitheatre

in

Britain.

Right: the Chester Amphitheatre under snow, January 2003

The

first amphitheatre

on

the

site

was

built

soon

after

the

establishment

of

the

great fortress

itself,

sometime

in

the

late

70s

AD

by the engineers of Legion

II Adiutrix

Pia

Fidelis ('Dutiful

and

Faithful').

Generally assumed to have been constructed of timber, recent research seems to indicate that this early amphitheatre was stone-built from the start. The Second Legion

were

posted

to

the

Danube

in

AD

86,

and,

towards

the

end

of

the

First

Century,

the

structure

was

progressively rebuilt

and enlarged by

their

successors, Legion

XX Valeria

Victrix ('Strong

and

Victorious').

However,

by

the

middle

of

the

Second

Century it

had

fallen

into

disuse. This

may

have

been

connected

with

the

temporary

posting

of

Legion

XX

northwards

to

assist

in

the

construction

of Hadrian's

Wall.

Upon

their

return,

they

continued

with

the

work

of

rebuilding

the Second Legion's

timber

and

turf

fortress,

and

by

around

275

AD,

their

amphitheatre

too had

been

restored

and

paved

with

sandstone

flags.

From

that

time,

it

stayed

in

constant

use

until

its

final

abandonment

around

the

year

350. There

is

evidence

that

it

underwent

numerous

structural

modifications

and

alterations

during

this

long

period.

Wherever

possible,

Roman

legionary

fortresses

were

constructed

to

a

standard

pattern:

a

playing-card

shaped

circuit

of

walls

aligned

north-south,

four

main

entrances

and

two

principle

roads

intersecting

in

the

centre,

where

were

located

the

headquarters (principia), the commander's residence

and

other major

administrative

buildings.

Along

with

barrack

blocks,

officer's

houses,

stables, workshops, granaries

and

bath

houses,

an

amphitheatre

situated

outside

the

walls,

generally

located,

as

here,

close

to

the

south-east

corner,

was

a

standard

feature

of

fortress

construction.

There

are

nineteen

Roman amphitheatres

known

in

Britain,

with,

doubtlessly,

more

waiting

to

be

discovered.

The

largest

is

at Maumbury

Rings,

Dorchester,

which

is

almost

a

third

larger

in

area

than

Chester's.

This,

however,

along

with

those

at Aldborough, Silchester, Chichester and Cirencester survive

only

as

earthworks. There

are

nineteen

Roman amphitheatres

known

in

Britain,

with,

doubtlessly,

more

waiting

to

be

discovered.

The

largest

is

at Maumbury

Rings,

Dorchester,

which

is

almost

a

third

larger

in

area

than

Chester's.

This,

however,

along

with

those

at Aldborough, Silchester, Chichester and Cirencester survive

only

as

earthworks.

All

but

three

of

these

amphitheatres

were

constructed

at

civil

settlements;

those

at Caerleon,

Chester

and York (this

latter

known

to

exist

but,

remarkably,

still

awaiting

actual

discovery)

are

the

only

ones,

to

date,

known

to

have

been

developed

as

part

of

legionary

fortresses.

This

'military'

type

of

amphitheatre,

of

which

Chester's

is

the

largest,

had

a

greater

arena

area

in

proportion

to

its

seating

compared

to

those

of civil

settlements.

They

were

mainly

used

for

military

training,

but

were also

opened to the general population for

'recreations'

(spectacula)

such

as

bull

baiting,

cock

fighting,

mock

hunts-

in

which

well-equiped

huntsmen

slaughtered

wild

animals

released

into

the

arena-

wrestling

and

boxing.

This

latter

was

a

popular,

though

brutal

sport

in

Roman

times.The

fighters

wore

no

protection,

and

instead

of

gloves

had

metal-studded

leather

thongs

wrapped

around

their

wrists.

Amphitheatres

were

also

used

for

the

public

execution

of

criminals-

both

military

and

civilian-

and

for

the

celebration

of

state

and

religious

special

events.

These

latter

would

have

featured

the

sort

of

gladiatorial

combat

(munera)

with

which

Hollywood

has

so

recently

once

again

made

us

familiar. A

relief

carving

on

slate,

found

nearby

in

Newgate

Street,

showing

a retiarius-

a

gladiator

who

fought

with

a

trident

and

net,

would

seem

to

confirm

that

this

type

of

activity

went

on

here

(you

can

see

a

drawing

of

it on

the

next

page).

Gladiators

could

be

of

either

sex

(a little known fact) and

were

drawn

from

the

ranks

of

slaves,

prisoners

of

war

and

petty

criminals,

to

whom

the

dangers

of

the

arena

may

well

have

been

preferable

to

the

alternative

fates

that

awaited

them

elsewhere.

Those

offenders

against

the

state-

including

many

early

Christians-

deemed

a

threat

to

Imperial

authority,

were

condemned ad

bestias,

'to

the

beasts'. These

unfortunates

were

left

tied

to

a

stake,

or

as

an

extra

'refinement'

were

pushed

naked

and

unarmed

into

the

arena,

where

wild

and

half-starved

animals

were

turned

loose

on

them. Gladiators

could

be

of

either

sex

(a little known fact) and

were

drawn

from

the

ranks

of

slaves,

prisoners

of

war

and

petty

criminals,

to

whom

the

dangers

of

the

arena

may

well

have

been

preferable

to

the

alternative

fates

that

awaited

them

elsewhere.

Those

offenders

against

the

state-

including

many

early

Christians-

deemed

a

threat

to

Imperial

authority,

were

condemned ad

bestias,

'to

the

beasts'. These

unfortunates

were

left

tied

to

a

stake,

or

as

an

extra

'refinement'

were

pushed

naked

and

unarmed

into

the

arena,

where

wild

and

half-starved

animals

were

turned

loose

on

them.

In

the

centre

of

the

arena

here

in

Chester,

a

series

of

postholes

set

into

narrow

gullies

(hidden

from

view

today)

suggest

the

possible

presence

of

a

timber

platform

of

some

kind-

possibly

a

scaffold.

This

structure

may

have

been

temporary,

being

erected

only

when

required. (It was this structure that encouraged the original assumption that the original amphitheatre had been timber-built).

What

became

of

the

amphitheatre

after

the

withdrawal

of

the

Legions

is

entirely

unknown,

but

it

does

seem

remarkable

that

the

site

of

a

structure

of

this

size

and

importance

could

have

vanished

so

effectively

as

to

remain

unrecorded

and

unsuspected

for

a

thousand

years.

But we refer again to York, the Roman Eboracum, the capital city of Britannia Inferior (the northern province of England)- where a great amphitheatre remains to this day tantalisingly lost somewhere beneath the modern streets. These

sites

would

doubtless

have

proved

a

valuable

source

of

quality

building

stone and other materials,

such

as

was used for

the

construction

of

the neighbouring St. John's

Church. The

alignment

of

medieval

streets

around

the

site

show

that

the

presence

of

the

ruins

long proved

an

obstacle

to

the

development

of

the

road

system

in

this

area. Little

St. John

Street, for

example,

has

for

centuries

followed

its

semi-circular

course

around

the

site

but

few

had

apparently

thought

to

question

why

this

should

be.

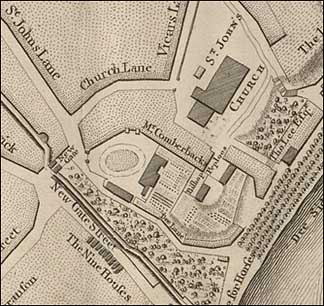

Here

we

see

the

site

in

a

small detail

from Wenceslaus

Hollar's map

of

1656-

but,

because

it

fails

to

show

the

devastation

we

know

occured

here

during

the

Civil

War-

probably

based

upon

the

earlier

work

of John

Speed and

others, such as the similar, but more roughly-sketched, detail from Daniel King's Vale Royal of England, above right.

Note

the

lane

running

from

directly

opposite

the

west

tower

of

St. John's

Church

and

ending

between

two

tall

houses

(?)

half

way

up

Souter's

Lane.

The

entrance

to

this

lane

was

situated

roughly

where

the

gate

to

the

controversial

new

County courthouse

(of

which

much

more

later)

is

now.

Due

to

Civil

War

bombardment

and

the

later

appearance

of

Dee

House

on

the

spot,

no

trace

of

this

lane

remains

today. Here

we

see

the

site

in

a

small detail

from Wenceslaus

Hollar's map

of

1656-

but,

because

it

fails

to

show

the

devastation

we

know

occured

here

during

the

Civil

War-

probably

based

upon

the

earlier

work

of John

Speed and

others, such as the similar, but more roughly-sketched, detail from Daniel King's Vale Royal of England, above right.

Note

the

lane

running

from

directly

opposite

the

west

tower

of

St. John's

Church

and

ending

between

two

tall

houses

(?)

half

way

up

Souter's

Lane.

The

entrance

to

this

lane

was

situated

roughly

where

the

gate

to

the

controversial

new

County courthouse

(of

which

much

more

later)

is

now.

Due

to

Civil

War

bombardment

and

the

later

appearance

of

Dee

House

on

the

spot,

no

trace

of

this

lane

remains

today.

Little

St. John

Street,

curving

around

the

north

of

the

amphitheatre,

was

first

recorded

as viculus

maioris

ecclesiae

Sancti

Johannis ('the

lane

of

the

greater

church

of

St. John')

and

is

shown

on Speed's

map of

1610

(reprinted

at

least

fourteen

times

between

1616

and

1770)

as

Church

Lane-

and Souter's

Lane,

to

the

west,

as Souterlode-

both

in

1274.

(a souter was

a

shoemaker

or

cobbler)

They

probably

followed

the

lines

of

Roman

streets

as

the

presence

of

the

amphitheatre

ruins

would

have

been

a

major

constraint

to

new

road

layouts

in

this

area.

The

site

of

the

amphitheatre

seems

to

have

long

remained

an

open

area

where

the

citizens

came

to

congregate,

play

and

worship,

becoming

slowly

filled

in

by

natural

erosion

and

its

sometime

use

as

a

refuse

dump.

A

bear

pit

here

also

provided

a

source

of

local

'amusement'.

The

arena

was

still

visible

as

a

shallow

depression

in

the

ground

as

late

as

1710,

when Dee

House (of

which

much

more

later),

was

built.

On the right we see the open area in a detail from Alexander De Lavaux's 1745 map of Chester. Below it, Dee House, set in its extensive gardens, is seen in the centre and labelled "Mr Comberback's". The curved road, following the ancient line of the outer wall of the amphitheatre, linking St. John's Lane (now St. John Street) and Vicar's Lane is here called Church Lane.

Within

half

a

century,

as

our

photograph

above

shows,

the

northern

half

of

the

site

had

disappeared

under

houses

and

the

remains

of

the

monument

beneath

quickly

became

lost

to

memory.

So

completely

did

it

disappear,

in

fact,

that W.

Thompson

Watkin in

his

influential Roman

Cheshire of

1889

wrote, "There

remains

the

interesting

question, where

was

the

amphitheatre?

A

station

or castrum of

of

the

dimensions

of

Deva

would

certainly

have

one...

It

would

certainly,

at

Deva

as

elsewhere,

be

outside

of

the

Roman

walls,

and

I

suspect

either

at Boughton or

at

the

'Bowling

Green'" (The

site

of

today's

so-called Roman

Garden,

just

across

Souter's

Lane

from

the

actual

site) "I

hardly

think

it

would

be

on

the

Handbridge

side

of

the

river,

though

we

may

look

for

discoveries

of

villas

in

that

area.

Time

will

probably

reveal

the

locality,

either

by

information

being

brought

to

light

from

old

manuscripts

or

or

from

actual

excavation

accidentally

taking

place

within

its

area". Which,

as

we

are

about

to

see,

is

exactly

what

did

happen... So

completely

did

it

disappear,

in

fact,

that W.

Thompson

Watkin in

his

influential Roman

Cheshire of

1889

wrote, "There

remains

the

interesting

question, where

was

the

amphitheatre?

A

station

or castrum of

of

the

dimensions

of

Deva

would

certainly

have

one...

It

would

certainly,

at

Deva

as

elsewhere,

be

outside

of

the

Roman

walls,

and

I

suspect

either

at Boughton or

at

the

'Bowling

Green'" (The

site

of

today's

so-called Roman

Garden,

just

across

Souter's

Lane

from

the

actual

site) "I

hardly

think

it

would

be

on

the

Handbridge

side

of

the

river,

though

we

may

look

for

discoveries

of

villas

in

that

area.

Time

will

probably

reveal

the

locality,

either

by

information

being

brought

to

light

from

old

manuscripts

or

or

from

actual

excavation

accidentally

taking

place

within

its

area". Which,

as

we

are

about

to

see,

is

exactly

what

did

happen...

Discovery

and

Danger

The

story

of

the

Chester

amphitheatre's

discovery

and

(partial)

excavation

and

of

the

numerous

threats

to

which

it

has

been-

and

continues

to

be-

subjected

is

one

that

has

touched

the

lives

of

hundreds

of

people

from

the

end

of

the

1920s

to

the

present

day.

As

we

shall

see,

it

is

little

short

of

miraculous

that,

poorly-presented

though

it

is,

so

much

of

this

internationally-important

monument

has

once

again

become

visible

to

us

today.

A

fortress

of

the

size

and

importance

of Deva would

certainly

have

possessed

such

an

amenity

and, as with Thompson Watkin,

its

existence

had

long

been

suspected

by

scholars.

One

of

these

was

a

classics

teacher

at

the

Chester King's

School, W

J 'Walrus' Williams (1875-1971),

who,

as

a

keen

amateur

archaeologist

(the

line

between

amateur

and

professional

was

not

so

rigid

as

it

is

now)-

and

member

of

the Chester

Archaeological

Society,

had

long

argued

for

the

amphitheatre's

existence.

And

indeed,

by

happy

fortune,

it

was

he

who,

in

June

1929,

while

examining

a

pit

dug

in

the

grounds

of

the Ursuline

Convent (of

which

more

later)

for

the

removal

of

a

large

holly

tree

in

preparation

for

the

installation

of

a

new

heating

plant,

observed

massive

pieces

of

masonry

and

immediately

realised

that

this

was

indeed

the

site

of

the

vanished

amphitheatre.

Actually,

it

is

said

that

the

first

man

to

set

eyes

upon

the

great

stones

was

Bill

the

convent

gardener,

who

at

first

thought

he

had

come

across

the

foundations

of

a

wall

or

old

house.

Bill

later

went

off

to

war

and

was

killed

somewhere

in

France.

But

what

a

moment

that

must

have

been

for

Walrus

Williams!

He

was

presented

with

further

evidence

of

what

lay

beneath

when

a

workman

unearthed

a

coin

of

Hadrian

in

his

presence,

and

his

findings

were

soon

after

confirmed

by

small-scale

trenching

carried

out

by P

H

Lawson.

In

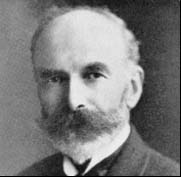

1930-1,

Professors Robert

Newstead (left) and J

P

Droop and

their

staff

from

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society

and Liverpool

University commenced

trial

excavations

in

order

to

ascertain

the

scale

of

the

buried

remains.

They

discovered

the

western

entrance,

parts

of

the

perimeter

and

arena

walls

and

the

arena

itself.

In

1934,

further

work

in

the

cellars

of St. John's

House-

of

which

more

later-

and

in

Little

St. John

Street

revealed

parts

of

the

northern

outer

wall. In

1930-1,

Professors Robert

Newstead (left) and J

P

Droop and

their

staff

from

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society

and Liverpool

University commenced

trial

excavations

in

order

to

ascertain

the

scale

of

the

buried

remains.

They

discovered

the

western

entrance,

parts

of

the

perimeter

and

arena

walls

and

the

arena

itself.

In

1934,

further

work

in

the

cellars

of St. John's

House-

of

which

more

later-

and

in

Little

St. John

Street

revealed

parts

of

the

northern

outer

wall.

National interest

in the work was considerable and progress was regularly reported upon within the pages of the London Times. Following are two such examples-

24th August 1930 "Some important discoveries have been made at Chester this week during excavations on the site of the Roman amphitheatre in the south-east angle of the city. The excavations are being continued under the direction of Professor R. Newstead on behalf of the Chester Excavations Committee. The operations have revealed a long section of massive Roman wall which is believed to date back to the first century, and Professor Newstead has concluded that it was probably one of the retaining walls of the side entrance to a Roman amphitheatre. This find, with the discoveries which were made last year, indicates that the amphitheatre was larger than that at Caerleon which is being preserved by the Office of Works. As is usual with the Roman buildings at Chester, the wall which the excavations have revealed rests upon solid rock. It stands about nine feet high and at the base measures six feet in thickness".

6th April 1931 "Further section of tbe arena wall of the Roman amphitheatre at Chester was revealed by excavations carried on under the direction of Professor Robert Newstead, F.R.S., last week. This new discovery removes any doubt as to the exact position of the structure. Although it has not been fully excavated, all the evidence leads to the conclusion that the wall has a depth of 16ft. and is about 18in. nearer the surface than the section previously found. Several "finds" have been made at various levels during the excavations. The most interesting is an exquisite example of a bronze second-century brooch with pin and spring intact and patina almost as brilliant as in the day of its casting. One level yielded much eighteenth-century pottery (chiefly slipware).. This level also revealed a number of beer jugs, which also appear to belong to the eighteenth century. Among various coins found are a second brass of Domitian, whlich had evidently been in circulation for a long time before it was dropped, for no trace of the original inscription remains; a small brass coin of Tetricus, probably minted between 268 and 273 A.D., and another third-century piece completely oxidized and with no traceable inscription.

The arena floor of the amphitheatre, as Professor Newstead now finds it, is covered with material evidently transported from building operations near by. Bits of bricks, broken tiles, slates and refuse have been found in layers above the surface of the floor. Discussing the signiflcance of the discovery of the new section of the arena wall, Professor Newstead said the relative position of the new flnd with the rest of the theatre was a factor in the suggested scheme for the complete excavation and preservation of the structure." Further discoveries must be made," he added, before we can actually decide what course to take."

Mr. C. R. Peers, Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments. examined the site last November on behalf of the Office of Works, and concurred with Professor Newstead that the future of the amphitheatre would depend to a large extent on the results obtained in the direction in which the new section has been found. If these were satisfactory he supported the suggested excavation and preservation of the whole site. Professor Newstead is continuing his excavations. He expresses no definite opinion yet as to how much this latest discovery may decide".

By

the

end

of

the

First

World

War,

with

the

growth

of

Chester

and

the

increasing

appearance

of

the

motor

car,

this

corner

of

the

city

was

constantly

congested

and

in

1926

plans

were

laid

to

replace

the

ancient Peppergate,

widen

the

road

leading

to

it

and

alter

its

course

so

it

left

the

town

in

a

'more

convenient'

straight

line. By

the

end

of

the

First

World

War,

with

the

growth

of

Chester

and

the

increasing

appearance

of

the

motor

car,

this

corner

of

the

city

was

constantly

congested

and

in

1926

plans

were

laid

to

replace

the

ancient Peppergate,

widen

the

road

leading

to

it

and

alter

its

course

so

it

left

the

town

in

a

'more

convenient'

straight

line.

As

may

be

readily

seen

from

this

photograph,

the

medieval

Peppergate

and

the

road

leading

to

it,

Little

St. John

Street,

were

at

this

time

extremely

narrow

and

hemmed

in

by

a

clutter

of

houses

and

small

factories,

such

as

'Poynton's

Famous

Pipe

Works', where clay pipes in the style of those used by the American Indians were manufactured, and considered by many to be the finest in England. The building on the left of the picture was the long-vanished Newgate Tavern.

(Go here to learn more about this and Chester's numerous other lost pubs).

The photograph would appear to be recording the final days of congestion in this area as the buildings on the right hand side are being removed to make way for the great changes to come. Compare

the

picture

with

the

modern

drawing

of

the Newgate on

the

previous

page.

It

was

actually

during

preparatory

work

for

this

road

that

the

true

extent

of

the

amphitheatre

site

was

established.

Despite

this,

some

sections

of

the

city

authorities

remained

adamant

that

the

road

would

be

built

as

planned,

claiming

that "they

could

not

afford

to

revise

their

plans

at

that

late

stage" (a

cry

that

has

echoed

down

the

decades

to

the

present

day,

as

we

shall

presently

see)-

and

also

that

the

cost

of

acquiring

and

demolishing the

properties

covering

the

northern

half

of

the

site would

be

prohibitive.

This,

of

course,

would

mean

the

almost

total

destruction

of

this

unique

treasure almost as soon as it had been found

and

resulted in

national

uproar.

The

City

Improvement

Committee

however,

to their credit, did delay

inviting

tenders

for

the

construction

of

the

new

road

to

allow

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society

time

to

raise

the

necessary

funds

to

divert

the

road

around

the

newly-discovered

monument-

the

(at

the

time)

considerable

sum

of

around £24,000.

The

debate

dragged

on

during

the

early

1930s

during

which

time,

as

with

many

of

today's

controversial

planning

proposals,

the

subject

was

rarely

absent

from

the

letters

pages

of

the

national and local

press.

This letter, for example, signed by a number of eminent local citizens including the High Sheriff of Cheshire, the Dean and Archdeacon of the Cathedral and the Chairman of the Council of the Chester Archaeological Society, appeared in the London Times on 19th March 1932:

"Sir, May we ask for a little space in which to make known the present situation of the Chester amphitheatre? Two years ago, on the site of new buildings outside the Newgate, extensive Roman masonry was found which Mr W. J. Williams identified as part of a Roman arnphitheatre. On the site of a by-pass road then planned, excavations made by Professor Newstead, F.R.S., amply confirmed the identification anid gave much valuable information about the structure. Recently the city council passed a recommendation to proceed with the road over the middle of the amphitheatre site. At this juncture we wish to lay stress on the immense historic and antiquarian importance of the work that is in danger of being buried for generations and perhaps irretrievably lost. It is no mere earthwork, but a massive stone structure existing still in the sections explored to a depth of between 7ft. and 9ft., in well-dressed ashlar masonry. The outer supporting wall is 9ft. thick, and the inner arena wall, 62ft. away, stands in good preservation. The importance of the work is also shown by its measurements, which put it on terms with the great amphitheatres of Nimes and Arles; for its outer measure is estimated at 315ft. by 284ft., and its arena floor at 190ft. by 161ft. The value of such a monument as a unique survival of Roman Britain is hard to over-estimate: and on all grounds we are sincerely anxious that nothing should be done to make its ultimate excavation more difficult, if not actually impossible. Admittedly this is not a time for lavish expenditure, and we do not urge that the whole site should necessarily be forthwith cleared for excavation. We do, however, wish to draw attention to the excellent possibility whlich presents itself of deflecting the road to the much more elegant and far safer line of the medieval Little St. John's Lane. We estimate that some £8000 would be sufficient for tlle acquisition of the sites necessary for widening this street and for the increased cost of road making. A further sum of £8000 would  enable us to offer the unencumbered site of half the amphitheatre to the Office of Works, who, as we understand, are willing to undertake the excavation and maintenance. And where such an important monument, an asset to the city and the nation, is in peril of being lost for ever we hope that the interest of the people will be aroused and that means may yet be found to make this most desirable alternative practicable. The respite brought about by the request of H.M. Office of Works to the city council enables us to appeal for contributions to effect the rescue of the site. Donations may be sent to the Hon. Treasurer, the Chester Roman Amphitheatre Fund, Lloyds Bank Limited, Chester". enable us to offer the unencumbered site of half the amphitheatre to the Office of Works, who, as we understand, are willing to undertake the excavation and maintenance. And where such an important monument, an asset to the city and the nation, is in peril of being lost for ever we hope that the interest of the people will be aroused and that means may yet be found to make this most desirable alternative practicable. The respite brought about by the request of H.M. Office of Works to the city council enables us to appeal for contributions to effect the rescue of the site. Donations may be sent to the Hon. Treasurer, the Chester Roman Amphitheatre Fund, Lloyds Bank Limited, Chester".

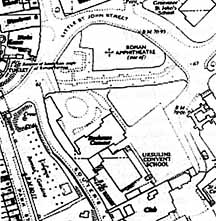

A

detail

from

the

1959

Ordnance

Survey

map

showing

the

site

of

the

amphitheatre

immediately

before

the

commencement

of

the

1960

excavation.

Clearly

visible

is

the

line

of

the

abandoned

road,

which

has

by

this

time

been

transformed

into

the

short-lived Amphitheatre

Gardens (illustrated

below

and here)

The national press reported that the appeal "has met with a remarkable response from all parts and from all classes at home and abroad. Subscriptions have been headed by the Duke of Westminster (grandfather of the current holder of that title) with £1,000, by Lord Wavertree, Lord Leverhulme, Lord Gladstone, and others. A schoolboy at Wrekin College sent 2s. 6d., and an unemployed workman handed in 2d. The local Chamber of Trade has taken the matter up with great enthusiasm. The elementary schools of Chester and neighbourhood have contributed useful quotas, the City and Counity School for Girls raising £41".

Some

well-aimed

publicity

ensured

continual

interest

and

comment

from,

among

others, Sir

Mortimer

Wheeler,

who

had

excavated

the-then

only

known

British

amphitheatre,

at Caerleon in

South

Wales

(smaller

and

less

sophisticated

than

Chester's)-

only

a

few

years

previously,

and

even,

in

November

1932,

the

Prime

Minister

of

the

day, Ramsay

MacDonald.

Sir

Mortimer

said

at

the

time, "From

an

archaeological

and

historical

standpoint

it

is

probable

that

the

scientific

excavation

of

this

structure

would

throw

a

new

light

upon

the

early

history

of

this

country." The Duke

of

Westminster was

also

a

signatory.

The

Grosvenor

Museum,

then

run

by

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society,

held

an

exhibition

of

Roman

artifacts

found

in

Chester

and

this

also

featured Jacob

Epstein's sculpture Genesis. The

Grosvenor

Museum,

then

run

by

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society,

held

an

exhibition

of

Roman

artifacts

found

in

Chester

and

this

also

featured Jacob

Epstein's sculpture Genesis.

(Epstein

is

probably

best

remembered

locally

for

his

statue

of

a

naked

man

standing on the prow of a ship which graces

the

main

entrance

of

Lewis'

department

store

in

Liverpool

city

centre- a traditional meeting place for generations of young people. Its official title is Liverpool

Resurgent-

but,

for

obvious

reasons it

is better

known

hereabouts,

as in the traditional saying, "Ah'll meet yer under Dickie

Lewis.")

At

the

same

time,

the

society,

which

celebrated

its

150th

anniversary

in

1999,

started

an

appeal

to

raise

the

necessary

funds

and

published

a

widely-distributed

leaflet

entitled Save

the

Chester

Amphitheatre! (which

you

see

reproduced

in

its

entirety here.)

The-then

Commissioners

of

Works

were

so

impressed

by

the

case

that

they

offered to

defray

the

cost

of

the

excavation

of

the

site

and

urged

the

city

council

to

delay

operations

so

that

the

road

could

be

diverted

and

properties

purchased

to

clear

space

for

further

excavation.

The

sum

of £8,000

was

to

be

raised

and

the

proprietor

of

the Plane

Tree

Cafe on

the Groves, Chester's riverside promenade,

offered £100

on

condition

that

49

others

did

the

same!

Despite

continuing

to

be

the

subject

of

considerable

national

and

international

criticism,

the

city

fathers

sat

tight

until,

in

1933

as

a

result

of

their

continuing

intransigence,

the

government

Ministry

of

Works

effectively

imposed

a

veto

upon

the

ill-conceived

road

scheme

by

refusing

loan

sanction.

Given

little

choice,

the

corporation

grudgingly

agreed

to

build

their

new

road around the

site-

and

also

to

spare

the

ancient

Wolfgate into the bargain.

They

erected

a

new

entrance,

designed

by

Sir

Walter

Tapper,

aptly

called

the Newgate,

next

to

it

instead,

which was

opened

to

traffic

in

1938. Despite

continuing

to

be

the

subject

of

considerable

national

and

international

criticism,

the

city

fathers

sat

tight

until,

in

1933

as

a

result

of

their

continuing

intransigence,

the

government

Ministry

of

Works

effectively

imposed

a

veto

upon

the

ill-conceived

road

scheme

by

refusing

loan

sanction.

Given

little

choice,

the

corporation

grudgingly

agreed

to

build

their

new

road around the

site-

and

also

to

spare

the

ancient

Wolfgate into the bargain.

They

erected

a

new

entrance,

designed

by

Sir

Walter

Tapper,

aptly

called

the Newgate,

next

to

it

instead,

which was

opened

to

traffic

in

1938.

The

site

saved,

funding

the

planned

excavation

remained

a

major

problem.

The

Chester

Archaeological

Society

formed

a

Trust

and

astutely

purchased

a

large

18th

century

brick

building, St. John's

House,

which

stood

on

the

north-east

portion

of

the

site

from

its

owners,

the

Anglo-American

Oil

Company.

From

May

1935,

they

leased

it

to

Cheshire

County

Council

for

successive

3

year

periods

and

invested

the

rents.

Unfortunately,

the

outbreak

of

the

war

in

1939

forced

the

postponement

of

plans

for

the

site's

imminent

excavation.

You

can

see

St. John's

House

in

the

centre

background

of

the

old

photograph above,

taken

from

the

same

spot

on

top

of

the

Newgate

as

the

one

at

the top

of

the

page,

showing

the

mass

of

buildings

that

once

covered

the

site.

In

the

foreground

you

can

see

the

lining

walls

which

were

all

that

was

ever

built

of

the

corporation's

ill-conceived

road

scheme.

A

correspondent

in

the

local

press

in

August

2000

reminisced

about

St. John's

House,

saying

the

entrance

hall,

which

was

on

the

north

side,

had

attractive

floor

tiles

and

outside,

on

the

east,

was

a

huge

well.

There

were

some

fine

trees

and,

during

the

war

years,

when

air

raid

shelters

for

St. John's

school

were

dug,

a

NAAFI

canteen

adjoined

the

Georgian

mansion, a large wooden building with a corrugated asbestos roof. For a few years after the war, it served as a social club for GPO (post office and telephone) workers.

You

can

see

some

photographs

of

the

old

house

and

read

about

its

many

and

varied

occupants here.

During

the

course

of

demolition,

evidence

of

an

earlier

building

came

to

light,

in

the

form

of

a

stone

inscription

dated

1664.

This

house,

whose

plan

was

unfortunately

not

recorded,

was

probably

built

during

the

restoration

of

the

area

outside

the Newgate following

extensive

devastation

during

the

Civil

War.

In

1892,

the

Rev

Scott,

incumbent

and

historian

of St. John's

Church,

reproduced

a

plan

of

the

church, "taken

from

two

plans

of

1589

in

the

British

Museum" which

showed

an

even

earlier

building

on

the

site,

'Mr

Marbury's

house',

which

may

have

been

in

existence

as

early

as

1470

but

was

presumably

destroyed

during

the

siege,

when

the

neighbouring

St. John's

churchyard

was

occupied

by

Parliamentary

troops

who

set

up

a

gun

battery

there

on

20th

September

1644.

Excavation

The

County

Council's

legal

department

occupied

St. John's

House

for

the

next

22

years,

but

relinquished

their

tenancy in

1957,

when

the

new County

Hall next

to

the

river

near

the Old

Dee

Bridge was

completed.

By

this

time,

the

income

generated

from

the

rent

of

St. John's

House

was

deemed

sufficient

to

allow

the

consideration

of

large-scale

excavation

of

the

northern

half

of

the

amphitheatre,

although

considerable

additional

funding

from

the

Ministry

of

Public

Works

was

also

necessary.

The

house

was

demolished

in

June

1958

and

excavation

of

the

site

commenced

in

1960

under Hugh

Thompson,

Curator

of

the Grosvenor

. The

County

Council's

legal

department

occupied

St. John's

House

for

the

next

22

years,

but

relinquished

their

tenancy in

1957,

when

the

new County

Hall next

to

the

river

near

the Old

Dee

Bridge was

completed.

By

this

time,

the

income

generated

from

the

rent

of

St. John's

House

was

deemed

sufficient

to

allow

the

consideration

of

large-scale

excavation

of

the

northern

half

of

the

amphitheatre,

although

considerable

additional

funding

from

the

Ministry

of

Public

Works

was

also

necessary.

The

house

was

demolished

in

June

1958

and

excavation

of

the

site

commenced

in

1960

under Hugh

Thompson,

Curator

of

the Grosvenor

.

Initial

work

was

designed

to

ascertain

the

exact

location

of

the

outer

walls

so

the

Corporation

could

fix

a

final

building

line

for

Little

St. John

Street

and

large-scale

excavation

followed

between

1960

and

1969.

The

site

was

transferred

into

State

ownership

in

1965

after

which

time

Hugh

Thompson's

successor

at

the

Grosvenor

Museum, Dennis

Petch,

took

over

much

of

the labour.

After

exposure,

the

remains

were

consolidated-

the

leaning

arena

wall

was

carefully

jacked

back

into

the

vertical

plane

in

small

sections.

Unfortunately,

the

outer

and

concentric

walls

had

been

too

severely

robbed

out

in

antiquity

to

permit

full

restoration

so

their

positions

were

indicated

by

thin

concrete

strips

laid

out

on

the

newly-created

grassy

bank.

Our

photograph

above

shows

the

excavation

in

progress.

Between

July

and

September

2000,

this

previously-excavated

half

was

subjected

to

a

further

small-scale

excavation

run

by

the

city

council, led

by Keith Matthews with

the

assistance

of

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society,

students

from

Chester

College

and

other

volunteers. Between

July

and

September

2000,

this

previously-excavated

half

was

subjected

to

a

further

small-scale

excavation

run

by

the

city

council, led

by Keith Matthews with

the

assistance

of

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society,

students

from

Chester

College

and

other

volunteers.

Two photographs from Spring 1958 of the 'Amphitheatre Gardens' which once landscaped part of the site- see map above- but which were removed when the excavation got under way. Another view of them is here and more are in our amphitheatre gallery...

During

this

dig,

much

evidence

came

to

light

of

damage

done

to

the

site

as

a

result

of

the

original

excavation

and

the

later

consolidation

of

the

remains

for

public

display

during

the

1960s

and

70s.

It

was

said

that

financial

and

other

restraints

meant

that

the

focus

of

work

was

strictly

upon

the

Roman

monument,

and

consequently

a

decision

was

taken

to

remove

all

post-Roman

deposits

mechanically

(ie

with bulldozers).

In

the

arena,

it

looks

as

if

the

Ministry

of

Works

had

actually shaved

off part

of

the

exposed

sandstone

bedrock

to

make

a

level

surface

onto

which

they

laid

their

'protective'

layer

of

gravel.

They

showed

even

less

respect

for

the

Roman

drains:

the

peripheral

drain

had

been

completely

replaced

by

a

concrete

feature,

while

the

axial

drain

had

fared

similarly

badly.

Worse

still,

there

was

a

herringbone

pattern

of

concrete

land

drains,

designed

(unsuccessfully)

to

improve

the

poor

drainage

of

the

arena.

Hugh

Thompson

later

expressed

regret

at

the

use

of

such

methods,

saying

that

the

clearance

"might

have

been

a

bit

ruthless

and

ham-fisted"...

It

is

sometimes

claimed

by

those

with

a

separate

agenda

that

the

structure

visible

to

us

today

is

a reconstruction-

and

such

would

also

have

to

be

the

case

when

the

southern

half

is

eventually

excavated.

This

is

not

the

case.

The

masonry

may

have

been

stabilised

and

repointed

in

places,

but

what

we

see

is

the

real

thing-

original, in

situ,

Roman

work.

The

Chester

Amphitheatre

was

eventually

opened

to

the

public

in

August

1972:

the

result

of

a

labour

of

love

by

hundreds

of

individuals

for

over

fourty

years. The

Chester

Amphitheatre

was

eventually

opened

to

the

public

in

August

1972:

the

result

of

a

labour

of

love

by

hundreds

of

individuals

for

over

fourty

years.

Perhaps

as

a

sign

of

things

to

come,

the

Chester

Archaeological

Society's

crucial

role

was

'overlooked'

and

today

is,

unforgivably, entirely

without

mention on

the

mouldering

information

panels

on

the

site.

Do

not

be

deceived

by

the

remaining

low

curved

wall

enclosing

the

small

central

arena-

the

Amphitheatre's

massive

exterior

wall

measured

320

by

286

feet

(95.7

by

87.2

metres)

and

stood

40

feet

(11.5

metres)

above

the

Roman

street

level,

around

twice

the

average

present

height

of

the

city

walls-

you

would

have

had

to

crane

your

neck

to

see

the

top!

The

interior

wall

facing

the

arena

stood

twelve

feet

high

and

the

arena

itself

measured

190

by

160

feet

(58

by

49.4

metres:

an

area

of

2230

sq

m).

At

regular

intervals

the

inner

and

outer

walls

were

connected

by

radial

walls

9

feet

thick.

An

inner,

'concentric'

wall

lies

2.1

metres

within

the

outer

wall

and

is

thought

to

have

formed

the

inner

wall

of

a

corridor

linking

the

entrances,

of

which

there

were

main

ones

to

the

north,

south,

east

and

west

as

well

as

a

series

of

eight

minor

entrances

(vomitoria)-

two

spaced

between

each

of

the

major

entrances.

The

building

would

have

comfortably

accomodated

around

8000

spectators.

The

entrance

into

the

arena

we

see

exposed

today,

the

northern,

was

the

one

through

which

the

animals

and

those

about

to

die

would

be

led,

as

well

as

those

about

to

participate

in

various

forms

of

gladiatorial

combat.

Their

bodies

would

be

dragged

out

by

horses

into

a

dark

passage

leading

to

the

dungeons,

animal

enclosures

and

changing

rooms

which

lay

across

the

modern

road-

and

which

were

exposed

to

view

when

the

GPO

switchgear

building

(soon to be a hotel) on

the

corner

of

St. John

Street

was

erected.

Next

to

this

entrance,

an

altar

was

found

in

situ,

dedicated

to Nemesis,

patron

Goddess

of

amphitheatres

and

Goddess

of

retribution,

by

the

Centurion Sextus

Marcianus "after

a

vision".

The

chamber

in

which

is

was

housed,

the

lower

parts

of

which

still

survive,

is

called

a Nemesium.

The

inscription

on

the

altar

is

as

follows:

DEAE:NEMESI

SEXT<IVS>:MARCI

ANVS:>EX:VI SV

Which

may be translated: "The centurion Sextius Marcianus (set up this altar)

to the Goddess nemesis after a vision" Which

may be translated: "The centurion Sextius Marcianus (set up this altar)

to the Goddess nemesis after a vision"

You

can

see

it

today

in

the

city's

excellent Grosvenor

Museum but

an

exact

copy

was

made

in

1966

and

stands

where

the

original

was

found.

(We're

sorry

to

say

that

in

August

2000,

this

replica

altar

was

broken

into

several

pieces

by

vandals.

It

was

'temporarily'

removed

by

English

Heritage

for

expert

repair and is yet to reappear.)

During the execution of criminals, animal fights and gladiatorial contests,

the presence of the altar would serve to remind those present that the laws

of Rome, carried out by men, were based upon divine rulings. Afterwards, Nemesis

would transport the souls of the guilty to Tartarus: the abyss of punishment

below Hades where the Titans were confined.

The currently-unexposed half of the Amphitheatre, facing the northern entrance,

was the 'better' part where the senior officers and principal citizens would

have been seated, although a tribunal, or private box, existed above

this entrance- the worn stone steps leading to it still exist.

The

newly-restored

Grosvenor

Museum

also

houses-

but

sadly

lacks

the

room

to

display-

the

hundreds

of

other

small

objects

found

amid

the

ruins-

pottery,

bits

of

jewellery,

broken

weapons,

coins,

carved

figures,

even

graffiti-

eloquent

reminders

of

the

long-dead

citzens

of

a

mighty

empire

who

once

mingled

together

on

this

spot.

On

a

coping

stone

which

was

once

situated

on

top

of

the

12-foot

high

arena

wall

was

found

the

insciption SERANO

LOCVS:

'Seranus'

place'-

inscribed

there

by

a

regular

attender

in

order

to

reserve

his

favourite

seat.

It is to be hoped that one day the city may acquire the means- and the will-

to put this remarkable collection of antiquities on public display- ideally

at, or close to, the amphitheatre where they first came to light...

This first part of the story of Chester's Amphitheatre, having grown inordinately,

has now been split into two- the second half is here- or read what the people think about current developments: reader's

letters to us and the local press...

|